by Sarita Dasgupta

Dear readers, I'm delighted to bring you Sarita Dasgupta's latest for Indian Chai Stories. Thank you, Sarita, for taking all of us to another time and place with this fascinating story of the Italian aristocrat who became a Darjeeling tea planter!

Darjeeling has some of the most picturesque tea estates with stunning views of the Himalayas, and the teas produced on the slopes of those estates have a unique flavour and aroma. Diehard ‘fans’ call them the Champagne of Teas. In the pioneering days of Darjeeling tea plantations, many intrepid Europeans arrived to make their fortunes. Most of them were British, but Louis Mandelli, a tea planter and amateur ornithologist who settled in the Darjeeling area in the mid-1800s, was an Italian aristocrat from Milan.Louis’ father, Jerome, was the son of Count Castel-Nuovo, a nobleman who owned property in both Italy and Malta. Filled with the nationalistic zeal propagated by Guiseppe Mazzini, Jerome is believed to have joined Mazzini’s newly formed secret society called ‘Young Italy’, created to fight for the unification of Italy. He became an ardent admirer and follower of the legendary Guiseppe Garibaldi, considered to be one of the greatest generals of modern times, and “the only wholly admirable figure in modern history”, according to the historian A. J. P. Taylor.

When Garibaldi sailed to South America to escape the death sentence pronounced on him after an uprising in Piedmont, Jerome accompanied him, leaving his wife and one-year-old son, Louis, in the care of his father in Milan. By the time he returned to Italy with Garibaldi in 1848, Louis was a young lad of sixteen.

It is not known why Jerome gave up his family name of Castel-Nuovo, and took up his mother’s surname, Mandelli, instead, but this he did, and his son was thereafter known as Louis Hildebrand Mandelli.

|

| Pix of Runglee Rungliot Tea Garden, c. 2008, by Partha Dey. All other pix sourced by the author from the internet. |

In one of Mandelli’s forty-eight letters found by British historian, late Fred Pinn, at the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, UK in 1985, he writes to his ornithologist friend, Andrew Anderson, the District Judge at Fatehgarh: “I have three gardens to look to, and large ones, and I am in the midst of manufacturing. I have been away from my place for the last 20 days to another garden under my charge as my Assistant there was doing everything wrong...I have no time to spare now a days.” This letter was dated 3 May 1873. In another letter dated 29 June 1873, he writes, “I could not find time...being so busy looking after three gardens under my charge, and each of them is at a great distance from one to another, so I have to remain at each for days and days, hence the delay.”

More interesting is another letter to Anderson, dated 25 June 1876, in which Mandelli sums up the challenges faced by a tea planter. He writes: “I can assure you, the life of a Tea Planter is by far from being a pleasant one, especially this year: drought at first, incessant rain afterwards, and to crown all, cholera amongst coolies, beside the commission from home to inspect the gardens, all these combined are enough to drive anyone mad.” I am sure that even a century and a half later, many a present-day tea planter will echo these words!

Lebong tea garden was established in 1842 by Harrisons Tea Company, and later merged with Mineral Springs tea garden, or “Dawai Pani” as it is called locally. The estate suffered many reversals and ultimately ceased to function as a tea production centre.

Chongtong (‘arrow-head’ in the local Lepcha language) was planted out by a British planter, and changed hands several times since then. The estate is doing well, producing organic tea which is popular among tea drinkers for its legendary flavour.

In 1871, Mandelli became part-owner of the 70-acre Bycemaree Tea Estate in the Siliguri area, along with Mr W.R. Martin. With the help of a hundred workers, they produced 10,800 pounds of tea in the first year, which almost doubled to 20,560 pounds in the second year. It is surmised that since Mandelli was already looking after three estates, he was a ‘sleeping partner’ in this enterprise, with Martin being the ‘Proprietor-Manager’.

Two years later, the duo bought the 160-acre Manjha estate, near Pankhabari. Manjha produced the world’s most expensive tea a few years ago, but unfortunately had to suspend all work in April 2018.

In 1875, Mandelli and Martin sold Manjha, buying and establishing the picturesque 200-acre Kyel Tea Estate in 1876. It is believed that when he first saw the place, Mandelli was struck by how “magical and mystical” it was. Kyel Tea Estate was sold to the Evandeon family in 1880, perhaps after Louis Mandelli’s untimely death. They managed it till 1955, when it was sold to Duncan Brothers, who in turn ran it for half a century. In 2006, the Chamong Group bought the tea garden.

When the daughter of the owners of Lingia Tea Estate was married to the owner of Kyel Tea Estate, (perhaps someone of the Evandeon family) a part of Lingia was given to the bride and groom as a wedding gift. This division was called Marybong (‘Mary’s place’ in the Lepcha language). Later, the merged estate was renamed Marybong Tea estate and so it remains. Marybong is now renowned for its first flush orthodox Darjeeling tea with its flowery aroma and unique flavour.

The rise in Louis Mandelli’s fortunes and his success as a tea planter can be gauged by his purchase of estates as well as a tract of land in the heart of Darjeeling town. According to ‘Darjeeling Past and Present’, Calcutta 1922, by EC Dozey, this area was renamed Mandelligunge, but all trace of it has now been lost. It is believed that Mandelligunge might have been what is now known as Nehru Road.

Unfortunately, calamities such as drought, excessive rain, and diseases like cholera, affected Mandelli’s fortunes, which began to go downhill, causing his health to suffer as a result. He died at the age of forty-eight in 1880, under circumstances now shrouded in mystery, and was buried in the Catholic Singtom Cemetery, quite close to Lebong, where he started his career as a tea planter.

His headstone bears the following inscription:

“Sacred to the memory of Louis Mandelli, for 17 years the respected Manager of Lebong and Minchee Tea Estate Darjeeling, who during his residence in this district, gained for himself an European reputation as an Ornithologist. He died on the 22nd February 1880, aged 48 years. This monument is erected by some of his numerous friends in India.”

Records in the local Roman Catholic church show that he married a lady called Ann Jones, possibly hailing from Calcutta, in 1865. They had five children – two boys and three girls. One of the sons, named for his father, worked as a travelling Inspector for the Railways. All three daughters lived on in Darjeeling well into the 1920s. It is also believed that the family may later have managed the legendary Firpos restaurant in Calcutta, established by another Italian – Angelo Firpos.

Louis Mandelli’s contribution to the tea industry in his seventeen years as a tea planter was not unremarkable – he started by managing three estates, and went on to own three of them. It is, however, his contribution in the field of ornithology as an amateur bird watcher and collector which is more significant.

Mandelli had no training or even a love for ornithology until he came to Darjeeling. In one of his letters to Andrew Anderson, he writes that if one didn’t have an interest in ornithology, “then I should say Darjeeling is not your place. The rains are frightful, the dampness horrible and the fog so dense that you cannot see few yards before you … the leeches will eat you alive, besides all other discomforts to go through.” Obviously, it was his new found interest in identifying birds that helped him cope with all the discomforts he mentioned in his letter.

(On a personal note - as someone for whom one of the chief pleasures of living on a tea estate was watching the different birds that flew around, I can fully understand Mandelli’s interest!)

It appears that his interest in collecting birds began in 1869. In one of his first letters to Anderson in 1873 he writes: “I am as yet a very poor ornithologist and quite ‘Kutcha’ about Raptores. Brooks (William Edwin Brooks -famous ornithologist and Mandelli’s mentor) is teaching me ‘in epistolis’ a good deal about small birds, and I dare say in due time I shall know the Birds of Prey also.”

In his next letter he says: “I am very poor in Grallatores, Natatores & Raptores, & to tell you the truth I know very little about them. I am going to study the Raptores when you send me yours.”

Mandelli spent a great deal of his spare time, and his own money, in documenting the native bird population. It is astonishing to note how he became an authority on birds in the course of less than ten years, considering what little reference material he had at his disposal! Much of his findings are still used and valued today, and his work helped put Darjeeling and its surrounding areas on the ornithological map. He generously gifted many of his specimens to museums in Darjeeling and Calcutta, the British Museum in London, and the Milan Museum. He was elected as a member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal in December 1877.

Mandelli exchanged specimens with renowned ornithologist, Alan Octavian Hume, and felt outraged when he thought that the latter had ‘stolen’ some of the rarer ones, claiming them as his own discoveries. However, Hume did give Mandelli credit for his finds, and even bought the latter’s bird collection after his death, presenting it to the British Museum. The specimens are now displayed at the Natural History Museum at Tring, Hertfordshire, which is around 30 miles away from Central London. The museum, which was the private property of Lionel Walter, 2nd Baron Rothschild, before it came under the Natural History Museum, London, was established in 1889. Mandelli’s bird specimens are among 4,000 of the finest collection of stuffed and mounted mammals, birds and reptiles exhibited there.

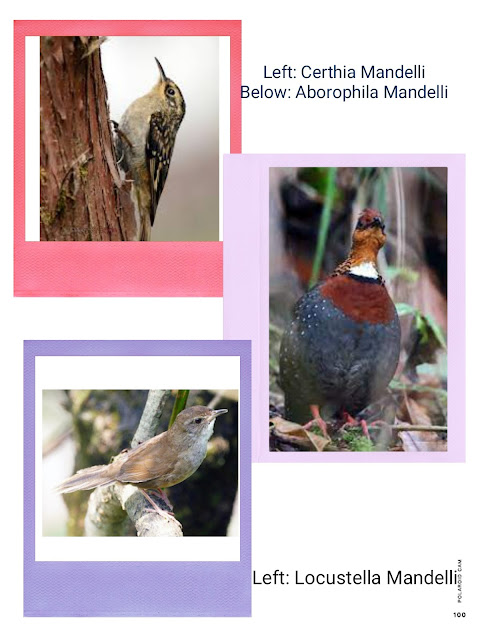

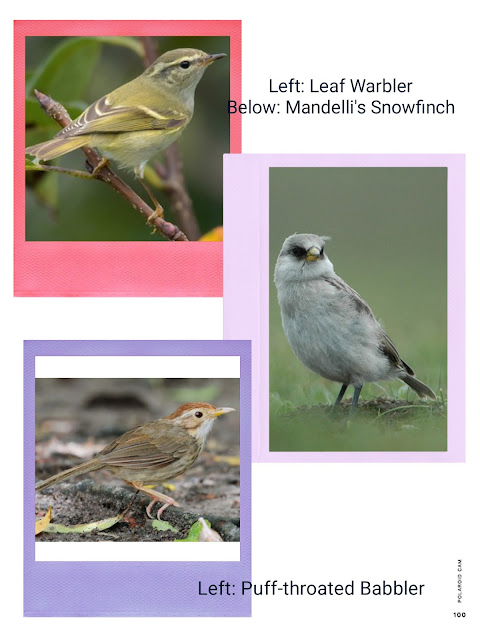

Some of the birds discovered by Mandelli and named after him are the Pellorneum ruficeps Mandelli, a puff-throated babbler, Arborophila Mandelli Hume, the red-breasted hill partridge, Phylloscopus Inornatus Mandelli Brooks, a leaf warbler, Certhia Mandelli, a tree creeper, Minla Mandelli, a tit-babbler, Locustella Mandelli, the russet bush warbler, and Mandelli's Snowfinch, the white-rumped snowfinch. He also discovered the now-endangered Myotis Sicarius or Mandelli's mouse-eared bat.Louis Mandelli has been gone for over a century and a half, but generation after generation of the birds named after him are still flying around, and will hopefully continue to do so for centuries to come.

A man could be immortalized for less!

Meet the writer: Sarita Dasgupta

| ||||

| Sarita enjoying a warm cup of Kawakawa tea in New Zealand. | Read about it here |

I have been writing for as long as can remember – not only my reminiscences about life in ‘tea’ but also skits, plays, and short stories. My plays and musicals have been performed by school children in Guwahati, Kolkata and Pune, and my first collection of short stories for children, called Feathered Friends, was published by Amazing Reads (India Book Distributors) in 2016. My Rainbow Reader series of English text books and work books have been selected as the prescribed text for Classes I to IV by the Meghalaya Board of School Education for the 2018-2019 academic session, and I have now started writing another series for the same publisher.

Do you have a chai story of your own to share? Send it to me here, please : indianchaistories@gmail.com.

Happy reading! Cheers to the spirit of Indian Tea!

ADD THIS LINK TO YOUR FAVOURITES :